15

Cell News 2/2015

on of erroneous microtubule-kinetochore attachments during

the early phases of mitosis. Such faulty attachments are cha-

racterized by kinetochores that are concomitantly attached to

microtubules emanating from the two opposing poles (so-called

merotelic attachments). This can also occur during a normal mi-

tosis by chance, but is usually corrected before anaphase onset.

If the rate of generation of merotelic kinetochore attachments

exceeds the rate of correction so-called lagging chromosomes

appear during anaphase. They reflect single chromatids which

harbor a kinetochore that is concomitantly bound to microtu-

bules from both poles (Fig. 1). As a consequence, such chro-

matids cannot properly be segregated onto a pre-determined

daughter cell and thus, repre-

sent a pre-stage of chromoso-

me missegregation (Gregan

et

al.

, 2011). Importantly, lagging

chromosomes are frequently

detected specifically in cancer

cells exhibiting CIN indicating

that erroneous and abnormally

stable microtubule-kinetocho-

re attachments that are not

properly corrected represent a

major source for chromosome

missegregation in human can-

cer cells.

In addition to supernumerary

centrosomes also other me-

chanisms might contribute to

the generation of microtubule-

kinetochore mal-attachments

(Nam

et al.

, 2015). For in-

stance, timely separation and

proper positioning of the two

centrosomes as well as correct

assembly and composition of

kinetochores are crucial for

proper interaction with micro-

tubules. Thus, various defects

can contribute to the genera-

tion of erroneous microtubule-

kinetochore attachments, but

whether they are indeed pre-

sent in cancer cells remains to

be shown.

Chromosomally instable

cancer cells exhibit incre-

ased microtubule dynamics

It is conceivable that highly

dynamic microtubules are pi-

votal for the faithful executi-

on of mitosis. In particular, the

plus ends of microtubules ex-

hibit ongoing transitions from

a growing to a shrinking state

(called "catastrophe") and

vice versa

(called "rescue"), which al-

lows the "search and capture" of kinetochores in order to achie-

ve efficient chromosome alignment (Kline-Smith and Walczak,

2004). Thus, abnormalities in microtubule dynamics are expec-

ted to result in impaired chromosome alignment and might re-

present a conceivable cause for CIN in cancer cells. Therefore,

we focused on potential abnormalities in microtubule plus end

dynamics in human cancer cells as a source for CIN (Ertych

et al.

,

2014). For our analyses we chose colorectal cancer (CRC) cells,

since this tumor entity is a prime example for a tumor exhibiting

CIN. In fact, about 85% of CRC cases are characterized by CIN

and high-grade aneuploidy while the remaining cases maintain

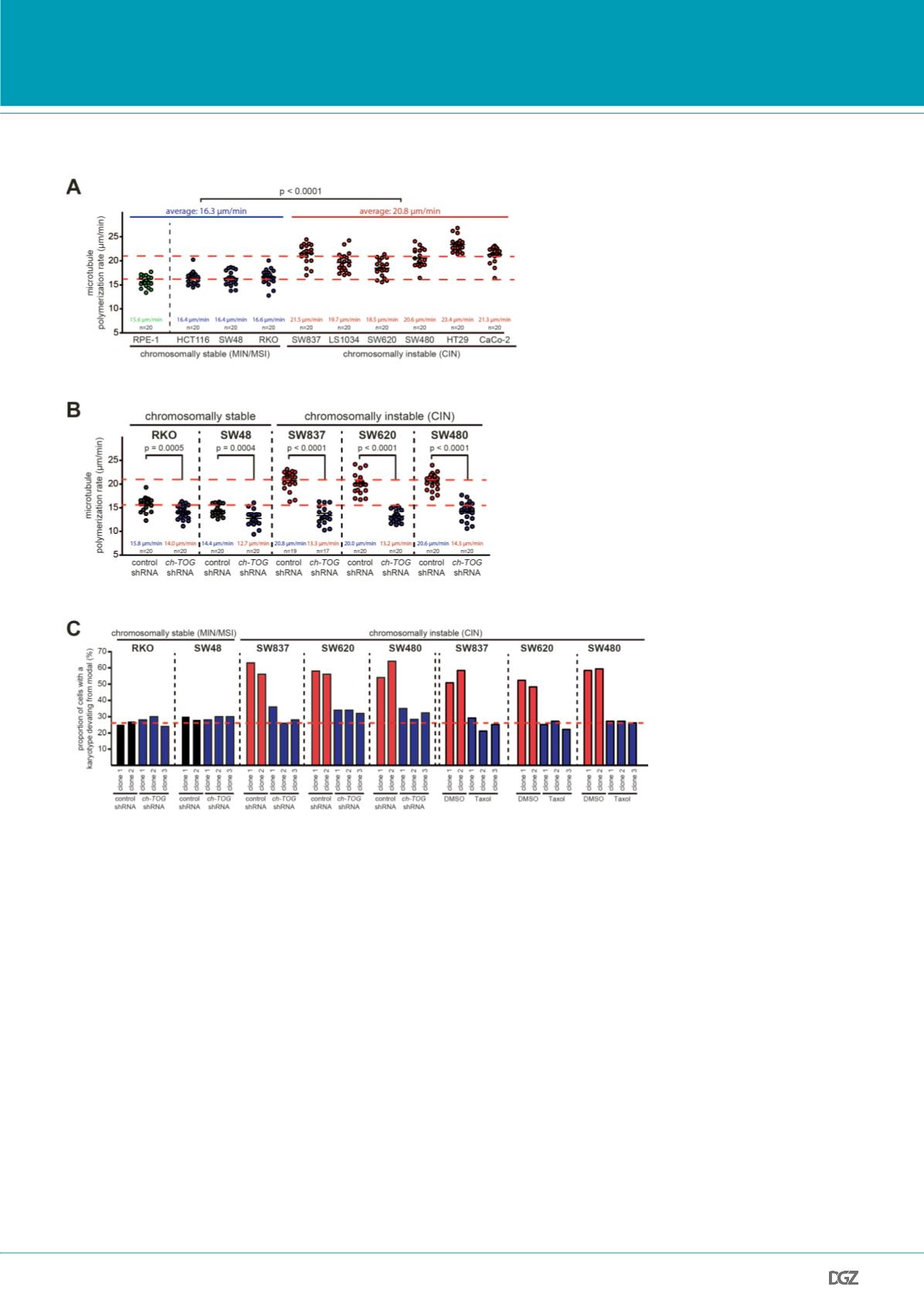

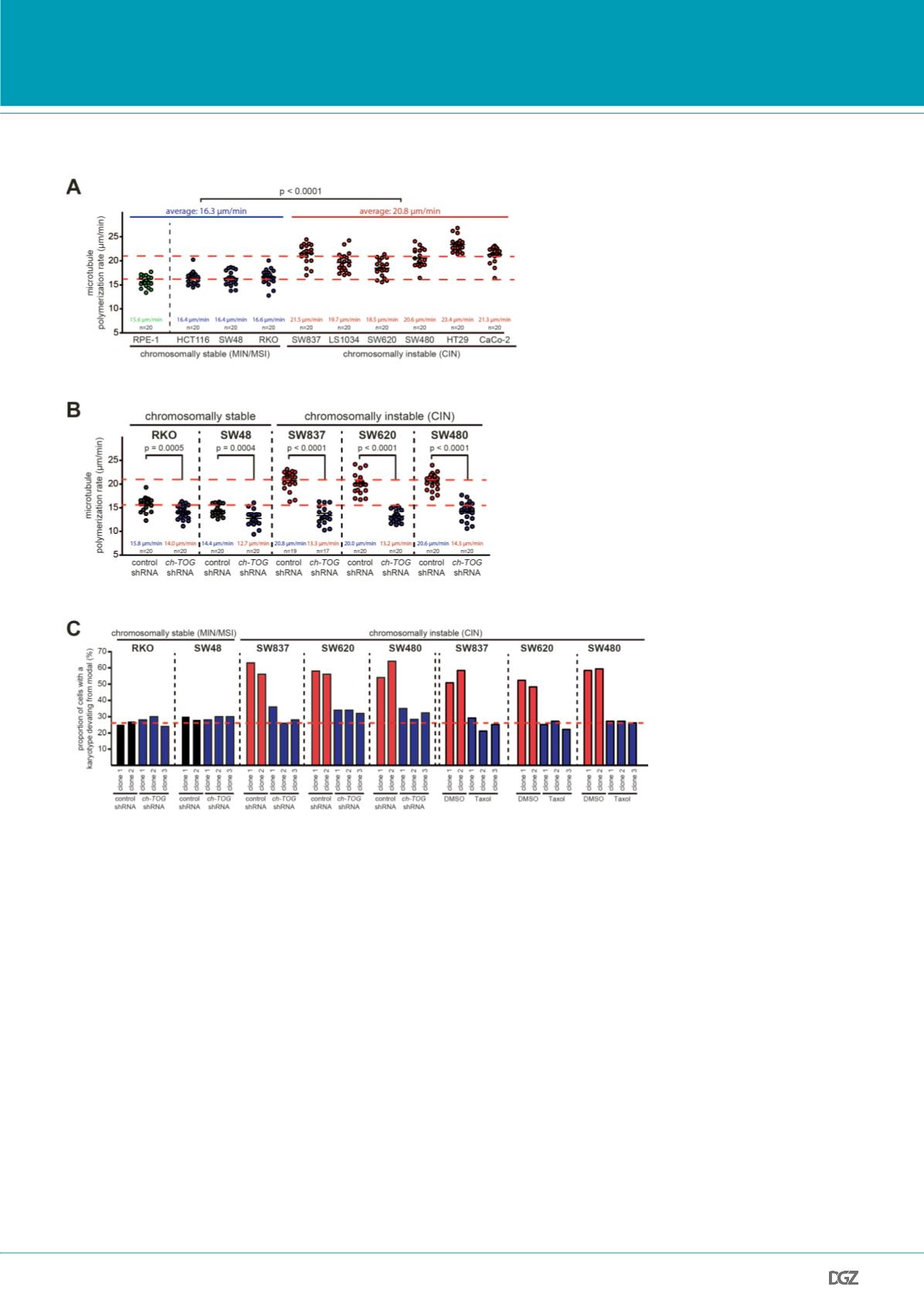

Figure 2:

Increased microtubule assembly rates trigger CIN. (A) CIN cells exhibit higher microtubule plus end

assembly rates. Measurement of microtubule plus end assembly rates was performed in various human colon

cancer cell lines exhibiting MIN/MSI or CIN by tracking EB3-GFP for 20 individual microtubules per cell (n=20;

t-test). (B) Restoration of normal microtubule assembly rates in CIN cells by partial repression of ch-TOG/CKAP5.

The indicated MIN/MSI or CIN cell lines were stably transfected with shRNAs targeting ch-TOG/CKAP5 and micro-

tubule assembly rates were determined. (C) Restoration of normal microtubule assembly rates suppresses CIN in

otherwise chromosomally instable cancer cells. Single cell clones were generated for the indicated cell lines and

numerical karyotype variability that evolved over 30 generations was determined as a measure for CIN. For each

clone the numerical chromosome composition for at last 100 metaphase cells was evaluated.

From: Ertych

et al.

, 2014.

PRIZE WINNERS